My dad was found in his home on Sunday, August 15, and I found out the following day. When I got the message from the ME’s office, I understood. I didn’t need to check the other message from my Aunt, saying that Dad died. I had just gotten in the car to make a Wendy’s run for my mom and I, and I immediately got back out. I needed to be with my mom. I walked back into her apartment, and blurted out “Dad died.”

Instantly, I was blank. Swiped clean of all motor and brain function. Somehow, I called the ME’s office back, and as the nice but gruff investigator told me he was afraid he had bad news, I found myself getting irritated. I know he was just doing his job, but didn’t he think I knew why the medical examiner’s office would be calling me about my dad? Didn’t he know I needed him to get to the point and tell me what the hell I was supposed to do?

How long had it been since I spoke with him? A couple of weeks. What health problems did he have? Yes, that makes sense. The coroner says hypertensive cardiac disease was the cause. He did tell me what I needed to do, and the office was open 24/7 to calls, and if I had any questions I could call, and I should contact the VA, and a funeral home, and sorry for your loss …

Everything blurs together. I talk to my aunt. The internal bleed my uncle has been suffering from is from cancer (which he now has for the second time in his life,) and they’re waiting on results from the biopsy. They won’t be able to do anything, physically, but they can help financially, and please keep us updated on whatever you decide. We trust you and support whatever decisions you make.

First, the apartment has to be cleaned out. The manager complains to me that the apartment smells, and I need to get the food out of the apartment as soon as I can, and she can give me until the end of the week, if that will help, and we can leave anything we can’t move or don’t want for her guys to move, and sorry for your loss, sweetie.

My husband goes with me the next day, and we can’t get into the apartment, because I’m not listed as an emergency contact. My uncle could come, though, or we could get a letter notarized saying we can enter the apartment. I have the urge to yell at the manager. I calmly say that I wish she’d mentioned this on the phone, and she says she assumed I had a key. I don’t explain that if I had a key, I wouldn’t have needed to call her to ask her all those questions in the first place before driving out there. “Is there anything else I should know,” I had asked. We walk out the door, I curse, and my husband, who now has my sanity in his hands, is calm and collected. He drives us to my aunt and uncle for another 25 minutes or so, and we get the one key my uncle has. We talk to the family. Everyone is sick. Everyone is struggling. Everyone prays for each other. Then, we go back.

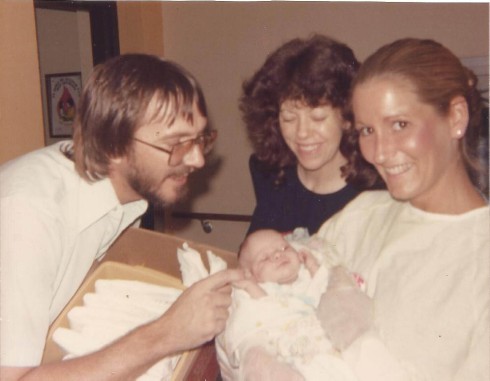

I won’t describe the state of the apartment. I will say that it infuriates me that our poor, our elderly, our disabled, and our veterans are treated with such disrespect. We cover our faces with masks and peppermint oil, armed with sprays and scrubs and bags, and I’m numb until I’m suddenly crying over a photo, a handwritten song, a report card from 4th grade. The apartment was never in such a state when I visited before.

It takes us until the end of the week, 4 days total – Tuesday and Thursday, Saturday and Sunday. The neighbors flock and tell stories, give condolences. Most are sincere, a couple debatable. Most are desperate for a microwave, a blanket, a chair, and are you taking that with you? We give. Dad would have given, and we don’t have room in my small car and his small truck to move everything. They give to us. A hug, some tea – are you thirsty? Can we help you move anything? We use trash bags for trash and for keepsakes. We tread a path in the grass from the patio to our parking spaces. We’re an army of strangers, and I’m glad to know they were looking out for him when they could. We left a bed frame, a sleeper sofa, filing cabinets. We pile the rest in our garage for the estate sale later.

Then the funeral home, the cremation. My mom goes with me. We’re not allowed to identify him. We sign papers and hand over checks and cash, and this is much more expensive than I expected for a cremation. I buy a beautiful box for him. I go back for death certificates, for ashes. Ashes are much heavier than I expected.

I create a wreath, a memorial candle, a shadow box. I scan photos, and create online memorials, and notify friends and family. I speak with a pastor who I’ve never met, who was Dad’s pastor, and he says come have church and would you like me to ask the members to bring a covered dish? It’s a potluck memorial in a barn. Then a potluck picnic in a local park the next week. One for one set of friends and family, one for another.

I don’t sleep well. I don’t sit still well. There’s not much time to be still, anyway, and business is an effective distraction. I plan a yard sale. The neighbors ask, can they participate? Is that allowed? Why not. The internet says that “multiple family sales” attract more customers, and we need the money.

The dog seems to think I need extra licks on my face. It makes me laugh.

I zone out, going somewhere that makes up for the lack of stillness and rest. I miss chunks of conversations, paragraphs of things I’m supposed to be reading.

I’m handling this all so well, they say. They couldn’t do it. They’d be a mess.

I don’t tell most of them about the appointment with my new psychiatrist days after it happened, and that he prescribed a drug most often prescribed to people with PTSD and nightmares. It’ll assist the other med I’m taking, he says.

He’s right. And I have a lifetime to grieve.